HLS Advocates for Human Rights Hosts Event Highlighting Atrocities Against Uyghurs

By Jasmine Shin & Samantha Lint

On March 9, 2020, HLS Advocates for Human Rights hosted a discussion at Harvard Law School on abuses committed by the Chinese government against Uyghur minorities in the Xinjiang region. HLS Advocates is a student practice organization which conducts human rights projects in partnership with NGOs around the world; raises awareness of human rights issues; and builds students’ capacity through trainings.

Speakers for the event included Sophie Richardson, China Director at Human Rights Watch (HRW), and Rayhan Asat, an alumna of Harvard Law School (LLM ‘16) who is of Uyghur origin. The discussion was moderated by Professor William Alford, the Director of East Asian Legal Studies at Harvard Law School. The event was co-sponsored by East Asian Legal Studies at HLS, the Program on Law and Society in the Muslim World, the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Inner Asian and Altaic Studies at Harvard, and the Harvard Muslim Law Students Association.

The Appalling State of Oppression in Xinjiang

The Uyghurs are a Turkic ethnic minority group who are predominately Muslim. They are one of the two largest groups in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) in Northwest China. Several Uyghur communities also live in neighboring countries in Central Asia, including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.

The Uyghurs have been long regarded as potential threats by the Chinese government due to their cultural and ethnic differences from the Han Chinese, the majority ethnic group in China, and demands for a separate state from some members of the Uyghur community.

Richardson emphasized the unparalleled scale of arbitrary detention of Uyghurs today, enabled by surveillance technology and driven by a misguided notion of sinicization. Over the past several years, HRW has documented the use of political re-education camps against Uyghurs by authorities in Xinjiang, where “torture, ill-treatment, denial of access to medical care, and intentional degradation” occur routinely. Richardson also highlighted the Chinese government’s surveillance of the Uyghur community – both as troubling on its own and as facilitating the detention program. For example, the Xinjiang police use an app “that gathers information about what is mostly perfectly legal behavior – how often [one] pray[s], when [one] talk[s] to [one’s] neighbors, whether [one] go[es] in the front or back door of [one’s] house.”

The Chinese government’s abuses against the Uyghurs, Richardson noted, are driven by “[its] mistrust of ethnic minorities” hidden behind a “security claim.” The Belt and Road Initiative may also be an additional motivating factor, as Xinjiang is an important region for the initiative due to its close proximity with countries to the west of China. Overall, the oppression of Uyghurs highlights the dangers of “sinicization – a fixed idea of what a ‘good’ Chinese citizen is – and a desire to produce a dissent-free society enabled by technology and surveillance.”

The Sudden Disappearance of a Harvard Alumnus’ Brother

Rayhan Asat (LLM ‘16), the first student of Uyghur ethnicity to graduate from Harvard Law School, shared the personal impact of this oppression. In March 2016, she was shocked to find out her brother, a social media platform entrepreneur, went missing shortly after returning to China following a trip to the United States to receive an award from the State Department. His detention was particularly troubling, Asat explained, because the state-owned media in China had previously praised her brother’s efforts to cultivate a greater understanding between the majority Han Chinese and other ethnic groups. He is now presumed to be in a re-education camp in Xinjiang. While it was a difficult decision for her to speak at this event given the fear of retribution, Asat felt she was called upon to share the truth, both as a sister and an attorney, and to draw attention to the Uyghur crisis at her alma mater.

Concrete Steps Forward for Accountability and Justice

Asat and Richardson both highlighted the need to hold the Chinese government accountable for its abuses against the Uyghurs and the challenges in doing so. Richardson pointed out that “[i]f any other government in the world was arbitrarily detaining one million people on the basis of ethnicity, we would be talking about accountability.” However, the situation is different with China, “because so many paths to accountability are through the UN,” and China has a track record of successfully blocking UN action on human rights violations. “If China is going to claim to be a good participating government in this [international] system,” Richardson noted, “it needs to open itself up to investigation and accountability.”

Given the difficulties of pursuing UN action, as well as the challenges in conducting an independent investigation within Xinjiang due to heavy surveillance, Asat focused on alternative methods to address the abuses. Citing the recently released “Uyghur for Sale” report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, which documented 83 companies that are implicated in profiting from Uyghurs’ forced labor, Asat called upon American corporations with products sourced from Xinjiang to end their complicity in the Chinese government’s abuses. Asat also urged these companies, such as Gap and Nike, to pull out from China in order to pressure the government to halt its human rights violations.

Asat argued that due diligence efforts and compliance policies are insufficient given the obstacles to internal investigations in China, where employees are often intimidated from revealing the truth. She also pointed out that certain industries in Xinjiang, especially the cotton industry, are well-integrated into the Chinese economy, and thus Western companies with products made elsewhere in China must also understand whether their supply chains involve products produced as a result of forced labor. She emphasized that Western corporations can pressure the government to halt its human rights violations.

Finally, Asat called on law students, consumers, and lawmakers to use their influence to force corporations to take action to ensure clean supply chains. Emphasizing that “we all can become agents of change,” and that justice cannot be achieved without the support of allies, she urged every individual, not just the Uyghurs, to join the fight for justice.

HLS Advocates for Human Rights thanks our speakers and co-sponsors for this opportunity to highlight the injustice in Xinjiang, and all those who attended the event for their interest and support.

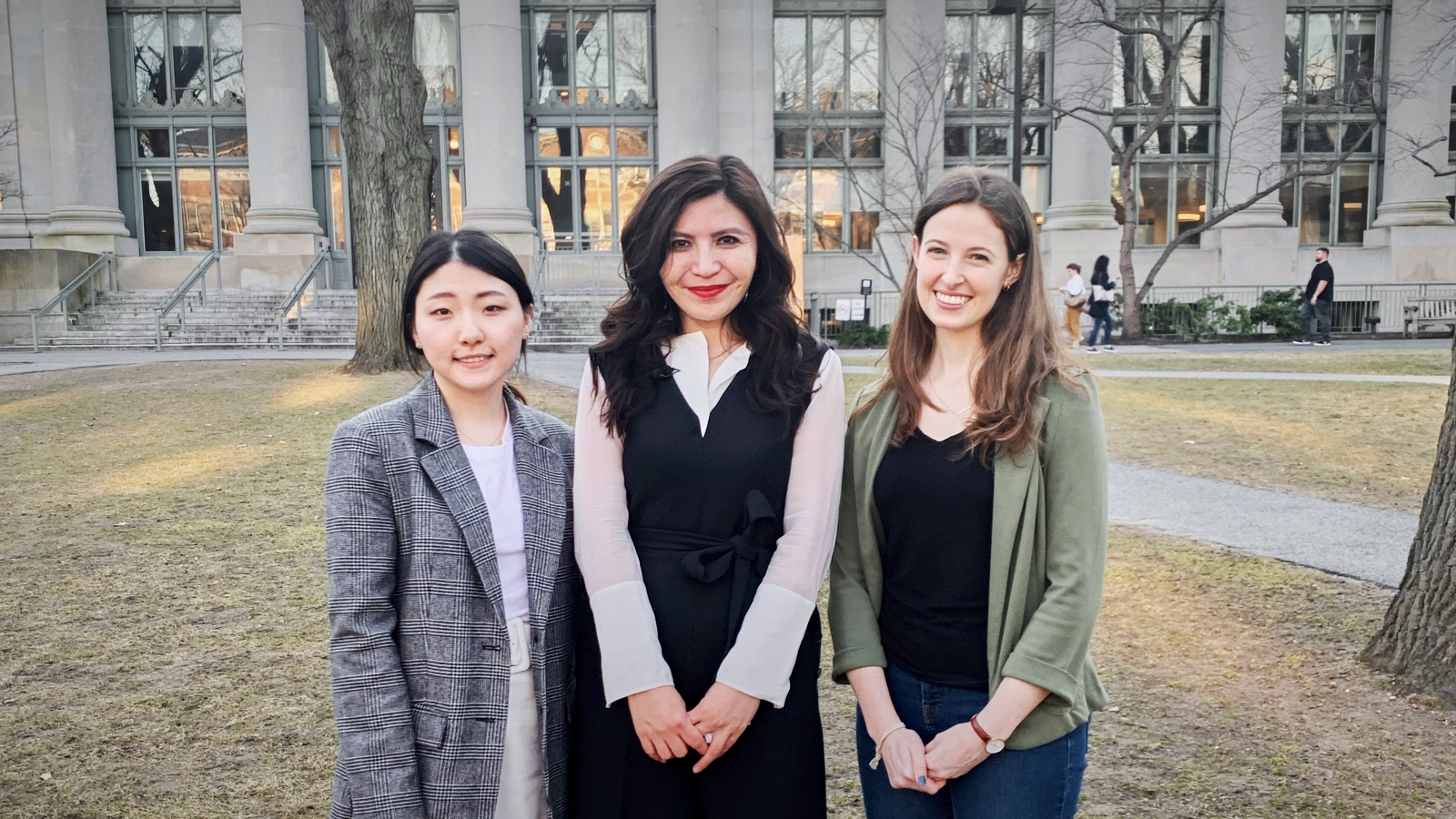

Rayhan Asat, LLM ’16 (center) met with HLS students Jasmine Shin, JD ’21 (left) and Samantha Lint, JD ’20 (right) after the event to discuss human rights violations in Xinjiang and future advocacy efforts.