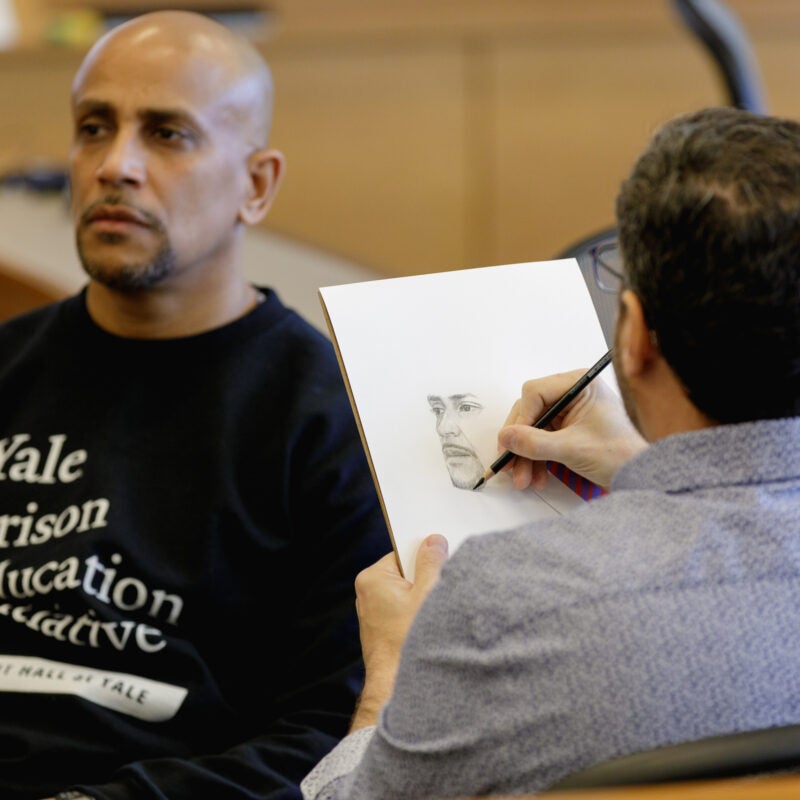

Elevating the voices of others

May 8, 2024

"I will forever be grateful for how HIP helped me and the broader policy team appreciate that however stacked the odds were, our Harvard education gave us the resources necessary to not just help individuals beat those odds, but to also strive for structural change that might provide a more fair and equitable immigration system," writes Bennett Stehr '24.