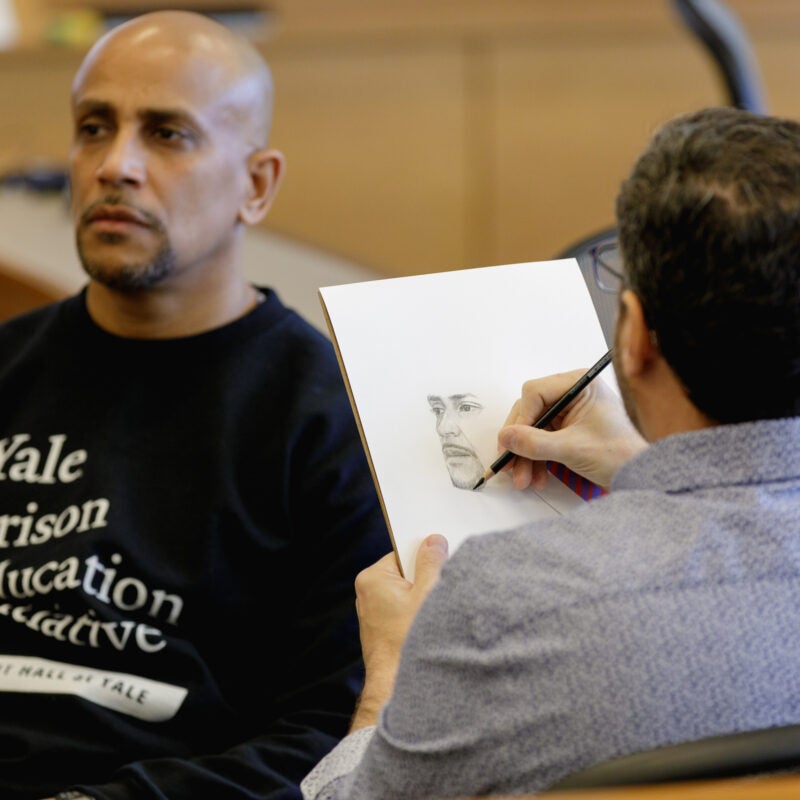

Harvard Defenders' Litman Symposium shines a spotlight on incarcerated artists

April 26, 2024

"We wanted people to tell us about their humanity, and about the way that the incarceration experience changed them," says Déborah Aléxis ‘25.

Clinic Stories News, stories, and updates from the world of clinical and pro bono work at HLS

Contact Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs

Website:

hls.harvard.edu/clinics

Email:

clinical@law.harvard.edu

April 26, 2024

"We wanted people to tell us about their humanity, and about the way that the incarceration experience changed them," says Déborah Aléxis ‘25.